Flows and Subflows

| Mule runtime engine version 3.8 reached its End of Life on November 16, 2021. For more information, contact your Customer Success Manager to determine how to migrate to the latest Mule version. |

| This page focuses on flows, the default structure with which you build applications in Mule. Note, however, that Mule also supports batch jobs for large and streaming messages. Batch jobs can be combined with flows in the same application, but their structure and functionality differs from that described here. To learn more, see Batch Processing. |

Overview

Mule applications are built around one or more flows.

-

Typically, a Mule application begins processing a message it receives at an inbound endpoint in a flow.

-

This flow can then either:

-

implement all processing stages, or

-

route the message to other flows or subflows to perform specific tasks.

-

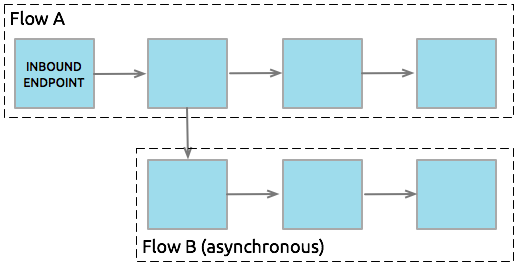

Relative to the flow which triggered its execution, flows and subflows can process messages either synchronously or asynchronously:

Advantages of Using Multiple Flows in an Application

-

Asynchronous Flow B can perform time-consuming tasks, such as writing data to an external database or emailing a message, without stalling Flow A, the flow that triggered its execution.

-

Flow A and Flow B can respond differently to errors.

-

Breaking up complex operations into a series of smaller flows or subflows makes applications – whether in a GUI or in XML code – easier to read.

-

The processing actions in a flows or subflows can be called and used by multiple flows in an application.

-

In clusters of Mule servers, messages can migrate between nodes when sent to an asynchronous flow. This allows for load balancing between nodes and higher performance of application. (See our advanced use case for an example.)

Types of Flows

When its execution is triggered by another flow in an application, a flow exists as one of three types:

1 |

Subflow |

A subflow processes messages synchronously (relative to the flow that triggered its execution) and always inherits both the processing strategy and exception strategy employed by the triggering flow. While a subflow is running, processing on the triggering flow pauses, then resumes only after the subflow completes its processing and hands the message back to the triggering flow. |

2 |

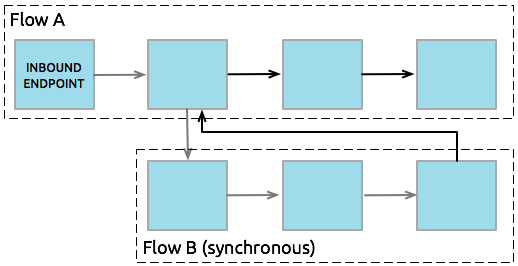

Synchronous Flow |

A synchronous flow, like a subflow, processes messages synchronously (relative to the flow that triggered its execution). While a synchronous flow is running, processing on the triggering flow pauses, then resumes only after the synchronous flow completes its processing and hands the message back to the triggering flow. However, unlike a subflow, this type of flow does not inherit processing or exception strategies from the triggering flow. This type of flow processes messages along a single thread, which is ideally suited to transactional processing. |

3 |

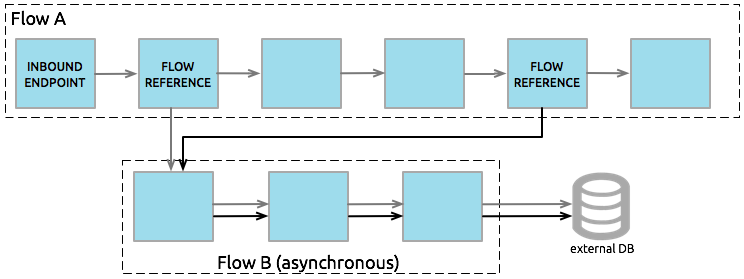

Asynchronous Flow |

An asynchronous flow simultaneously and asynchronously processes messages in parallel to the flow that triggered its execution. When a flow passes a message to an asynchronous flow, thus triggering its execution, it simultaneously passes a copy of the message to the next message processor in its own flow. Thus, the two flows – triggering and triggered – execute simultaneously and independently, each finishing on its own. This type of flow does not inherit processing or exception strategies from the triggering flow. This type of flow processes messages along multiple threads. |

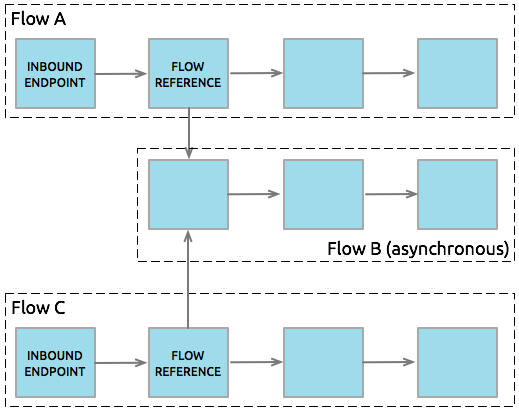

All three types of flows are identified by name and, thus, can be called as often as needed via flow reference components in other flows. For example, if an asynchronous Flow B’s job is to update a database with logged data, any number of other flows can feed data to be logged into Flow B to update the same database (see image below). Because it processes messages asynchronously from any flow that triggers its execution, Flow B doesn’t hold up the processing of any of its sister flows. Read more about Triggering Flows below.

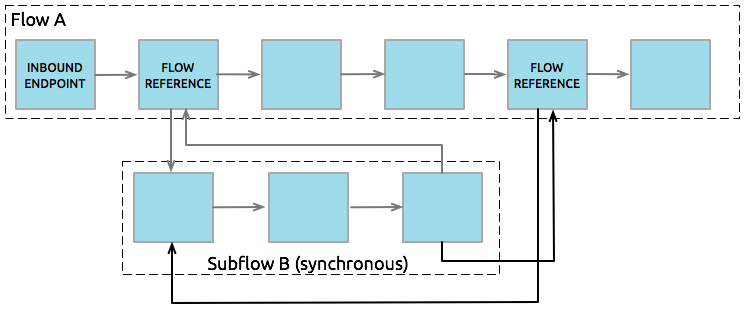

Subflows

Subflows, which always run synchronously, inherit both the processing strategy and exception strategy of the flow that triggered its execution. Compared to keeping all message processing activity contained within a single flow, using a subflow to complete some message processing activities offers a few advantages:

-

A subflow can isolate logical processing blocks, making the graphical view more intuitive and the underlying XML code much easier to read.

-

Subflows are ideally suited for code reuse, so you can write a particular block of code once, then reference the same subflow repeatedly from within the same application. The diagram below offers an example of a subflow that is executed twice by different flow reference components in the same flow.

-

Subflows inherit the processing strategies and exception strategies of the flow that triggers it, which means you don’t have to define these same configuration details again when building a subflow.

Note that a flow:subflow relationship is an n:_n_ relationship. In other words, a flow can reference several subflows to complete synchronous processing tasks, and a subflow can have several triggering flows. The subflow inherits the processing and exception strategies from whichever flow triggered it’s execution. Where you do not want a subflow to inherit any parameters, you can simply use synchronous flows.

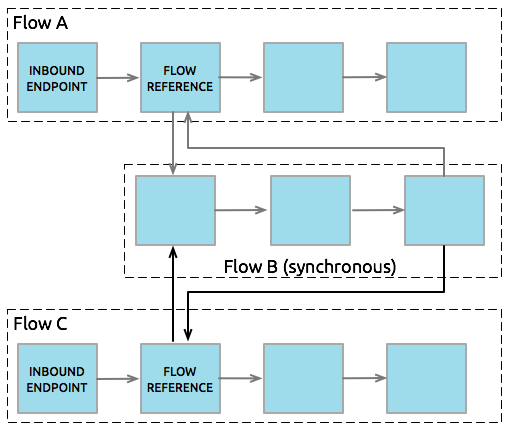

Synchronous Flows

Like a subflow, a synchronous flow processes messages synchronously relative to the flow that triggered it. Unlike a subflow, a synchronous flow does not inherit the triggering flow’s processing or exception strategies. Thus, you can set the synchronous flow’s processing and exception strategies to behave differently from the exception strategy you configured for the flow(s) which triggered its execution.

Moreover, because it does not inherit a triggering flow’s parameters, a synchronous flow can accept calls from multiple flows within an application (see image below) using its own processing and exception strategies. In other words, a flow:synchronous flow relationship is n:1. (Of course, a flow can call multiple synchronous flows, so the relationship could really be described as n:n.)

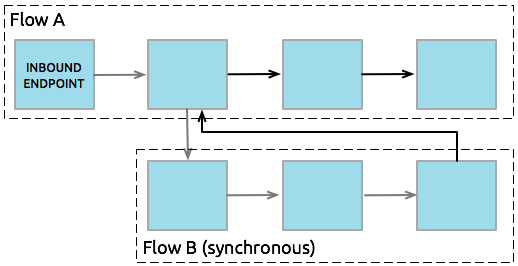

About Synchronous Message Processing

When a flow triggers a synchronous flow or subflow, it passes programmatic control to the triggered flow and suspends its own message processing activity. For example, when the synchronous Flow B completes its sequence of message processing events, it passes programmatic control back to Flow A. The message that exits Flow B replaces the message in Flow A (see image below).

Since the Flow A and Flow B hand off programmatic control to each other and, by implication, all processing occurs on the same thread, each event in the message processing sequence can be tracked. This setup is ideal for ensuring transactional processing.

|

Transactional Processing Transactional processing handles a complex event (such as the processing of an individual message by a Mule application) as distinct, individual event that either succeeds entirely or fails entirely, and never returns an intermediate or indeterminate outcome. Even if only one of the many message processing events in a Mule flow fails, the whole flow fails. The application can then “rollback” (i.e. undo) all the completed message processing steps so that, essentially, it’s as though no processing has occurred at all on the message. Sometimes, in addition to rolling back all the steps in the original, failed processing instance, the application can recover the original message and reprocess it from the beginning. Since all traces of the previous, failed attempt have been erased, a single message ultimately produces a only single set of results. Typically, transactionality is difficult to implement for Mule flows that transfer processing control across threads, which occurs for most types of branch processing. However, certain measures (such as using VM endpoints at the beginning and end of each child flow that does not run on the flow’s thread) can ensure that each of its triggered flows executes successfully as a unit. Note, however, that this architecture does not ensure that each message processor within one of the triggered flows completes its task successfully, only that it behaves as a unit. Read more about setting up Transactional units in Mule applications. |

Asynchronous Flows

Asynchronous flows begin processing a message when triggered by another flow. Since this type of flow does not need to return data to the flow which triggered it, it can execute simultaneously to its triggering flow. In other words, when Flow A triggers asynchronous Flow B, it neither passes programmatic control to the asynchronous flow, nor does it pause its own message processing. In the image below, the asynchronous flow uses its own exception strategy and can be called multiple times within a single flow or many times by multiple flows to inject data into an external database.

Triggering Flows

The following table details the component to use in a flow to call other flows.

| Type of Flow | Component | Execution Relative to Triggering Flow |

Exception and Processing Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

Subflow |

Flow Reference |

synchronous |

inherited |

Synchronous Flow |

Flow Reference |

synchronous |

not inherited |

Asynchronous Flow |

Flow Reference wrapped within an Async Scope |

asynchronous |

not inherited |

See Also

-

Examine an advanced use case showing a more complex flow architecture that uses several child flows.

-

Read about some alternative ways to control message processing within a flow using routing message processors.

-

Refer to the Flow Reference Component Reference and Async Scope.

-

Read more about Flow Processing Strategies.

-

Read more about setting up transactional units in Mule applications.